Leandro Muniz: In 2017 and it finished in 2019. It was curated by Patricia Carta, Adriano Pedrosa and Olivia Ardui. And it has the most clothes that could potentially be used and produced. In the second (2019-2020, curated by Lilian Pacce, Adriano Pedrosa and Guilherme Giufrida) and third (2021-2022, curated by Hanayrá Negreiros, Adriano Pedrosa and myself), this subject of clothes in the museum goes to another level. They are not easily wearable. For example, a piece by Sonia Gomes and Gustavo Silvestre has a false opening for the arm, so this place of clothing is more on the edge of the sculpture. Then we arrive to a case like Jum Nakao and Edgard de Souza, who sewed his piece directly to a MASP 's mannequin.

L: Some are rented but the MASP’s ones are all black.

L: Some of them were there, – and were reformed to be presented now.

L: Since the beginning of the museum, we have had [Pietro Maria] Bardi's desire to have a fashion collection, and he has had some failed attempts.

L: First there was a desire to create a session of Latin American fashion customs, that some documents from 1948/1949 attest, since he was talking to museums in Latin America trying to get donations that didn't work out. Then he asked the local elite to donate pieces from French designers to form a collection, a costume session inspired by the MET Costume Institute. In the 50s he could already manage to do some things, there was a Dior fashion show in the first building of the museum, in São Paulo downtown. There was a show called “The History of Italian Fashion” which weren't necessarily period pieces, for example, there was a Renaissance costume that was the first clothing piece to enter the collection... Before the entrance of the 79 Rhodia pieces, in 1972 there was a model by Salvador Dali called “Costume of the Year 2045” made in Brazil , by a Dior designer that also entered the collection. So fashion in MASP’s collection has a long history, but the model of Rhodia, in which artists and designers worked somehow together is the starting point to the MASP Renner project.

L: There’s a Jeanne Lanvin dress, some donations from Brazilian designers and Clothing objects yet to be studied. In total, there are 600 fashion items in MASP’s collection and Rhodia is the most significant for the time, since they were making clothes made by the so-called sewers from printed fabrics by local artists, which, had a super relevance at the time. And now MASP Renner, in which we have pieces made by artists and designers directly for the museum collection, which is quite unique in the history of fashion and its entrance into museums

L: Since the 1910s there have been partnerships between designers and artists, like Paul Poiret and Raoul Dufy, the Russian constructivists artists making clothes in the 1920s.... There was a Biennale in 1996 in Florence about these subject...

L: But there was never a collection on this subject: a collection without previous circulation created from this point of contact between artists and designers.

L: Both Patricia Carta, Lilian Pacce and Hanayrá also have this connection with the publishing market that Vreeland had. I find it interesting to think about how fashion curators are connected and move between curation, research, the world of communication, magazines, and looking at visual essays with text. It's cool to think about a historical alignment.

L: This documentation thing is very curious. In the catalogue there is my text, there is another by Maria Claudia Bonadio, a guest, , and those by the fashion curators. I also made this equation of what is in the work of artists and designers and the result of these partnerships. For example, photo of Alexandre da Cunha's work, a photo of Reinaldo Lourenço’s piece, a text,and when you turn the page, the works that appear in the exhibition. It's curious how the artists have everything documented and the designers have absurd gaps in information, where it came from, which has to do with your comment about a lack of memory preservation in the field of fashion. One of the areas of the MASP Renner project is thinking about memory, since an outfit made for the museum is made to last forever. The memory implicit in it was already given from the beginning. I think this memory permeates the whole, both in the narratives that the clothes articulate, to how they were made and for what type of body. Fashion brings the way of doing things, the origins of the material. And all of these elements preserve memories somehow.

L: Showing fashion is very difficult. It has specific presentation conditions in terms of temperature, light and humidity. These clothes, for example, after the end of the show, they have to remain without receiving light for months. The fabric, like our skin, loses pigment and then materiality and falls apart when exposed to light. That's why the Rhodia collection is not permanently exposed. There is an international museum agreement that defines the technical light for drawings and fabrics. It's really a challenge to exhibit fashion, and museums in Brazil already have challenges in themselves.

L: It has a vibe, everything looks beautiful, the textures become brighter, the colours too...

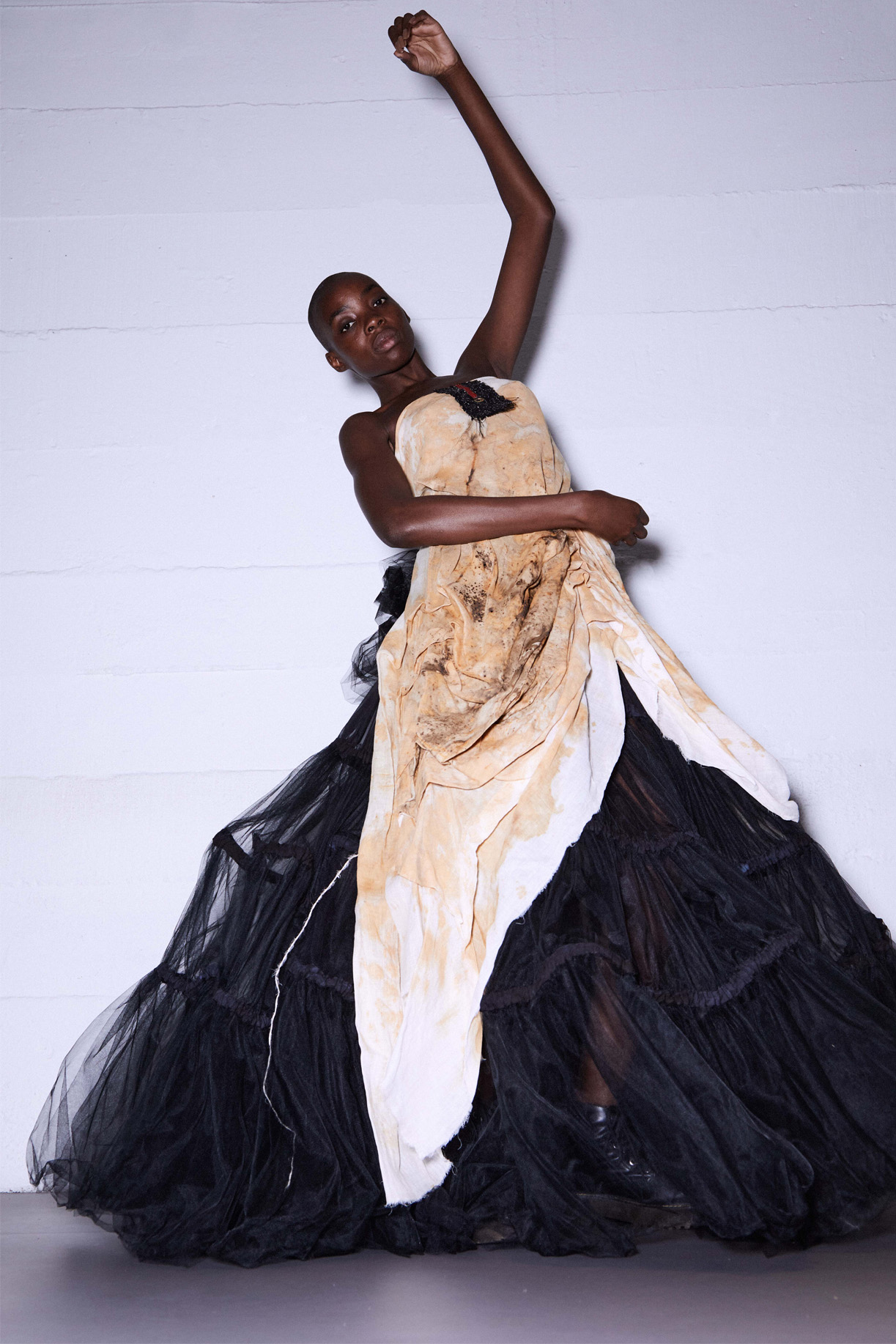

L: We thought a lot about a way to get away from two analogies that are common in fashion exhibitions: the catwalk and the showcase. These amoeboid shapes were too much to handle this square space, thinking about getting away from the linearity of the catwalk and the associations that this brings, like evolution and linearity, and getting away from a linearity that the project does not have. Even though it has three seasons, we have silhouettes that refer to the future, like avaf and Amapô or Vicenta Perrotta and Randolpho Lamonier. Others refer to the 19th century, because they have a crinoline. It is a less fixed temporality.

L: 45 sketches and three documentaries that I produced over the time and in which Cássia Tabatini also participated in the photos. These additional materials gave unity to the project and made the editing process much easier. For the public, it is possible to access both the process and these clothes in the only moment they were worn by bodies.

L: I entered the museum’s curatorial team to work at MASP Renner, in the third season along with Hanayrá Negreiros and Adriano Pedrosa, in 2021 So this implies that this is a long-term research, two and a half years, almost a master's degree in an extended research that allowed me to put the project in perspective with the history of fashion, with the history of art, with the history of museology in fashion and, especially, MASP ’s history. At the same time, it allowed me to live with the artists and designers and interview them all for the catalogue and the documentaries. It was a cool experience, getting to know the pairs, and understanding their connections, to write all the texts. There is a great variation that makes it cool to understand each work, each project, and how the works connect. Fashion is cool, there's a lot of knowledge accumulated in an outfit: geometry, updated modelling and the more conceptual perspective, such as signs of gender, class, religiosity, rebellion or acceptance.